David

P Goldman

FirstThings Number 193 May 2009

Three generations of economists immersed

themselves in study of the Great Depression, determined to prevent a recurrence

of the awful events of the 1930s. And as our current financial crisis began to

unfold in 2008, policymakers did everything that those economists prescribed.

Following John Maynard Keynes, President Bush and President Obama each offered

a fiscal stimulus. The Federal Reserve maintained confidence in the financial

system, increased the money supply, and lowered interest rates. The major

industrial nations worked together, rather than at cross purposes as they had

in the early 1930s.

In

other words, the government tried to do everything tight, but everything continues

to go wrong. We labored hard and traveled long to avoid a new depression, but

one seems to have found us, nonetheless.

So

is this something outside the lesson book of the Great Depression? Most

officials and economists argue that, until home prices stabilize, necrosis will

continue to spread through the assets of the financial system, and consumers

will continue to restrict spending. The sources of the present crisis reach

into the capillary system of the economy: the most basic decisions and requirements

of American households. All the apparatus of financial engineering is helpless

beside the simple issue of household decisions about shelter. We are in the

most democratic of economic crises, and it stems directly from the character of

our people.

Part

of the problem in seeing this may be that we are transfixed by the dense

technicalities of credit flow; the new varieties of toxic assets, and the

endless iterations of financial restructuring. Sometimes it helps to look at

the world with a kind of simplicity. Think of it this way: Credit markets

derive from the cycle of human life. Young people need to borrow capital to

start families and businesses; old people need to earn income on the capital

they have saved. We invest our retirement savings in the formation of new

households. All the armamentarium of modern capital markets boils down to

investing in a new generation so that they will provide for us when we are old.

To

understand the bleeding in the housing market, then, we need to examine the

population of prospective homebuyers whose millions of individual decisions

determine whether the economy will recover. Families with children are the

fulcrum of the housing market. Because single-parent families tend to be poor,

the buying power is concentrated in two-parent families with children.

Now, consider this fact: America's population

has risen from 200 million to 300 million since 1970, while the total number of

two-parent families with children is the same today as it was when Richard

Nixon took office, at 25 million. In 1973, the United States had 36 million

housing units with three or more bedrooms, not many more than the number of

two-parent families with children--which means that the supply of family homes

was roughly in line with the number of families. By 2005, the number of housing

units with three or more bedrooms had doubled to 72 million, though America had

the same number of two-parent families with children.

The number of two-parent families with children,

the kind of household that requires and can afford a large home, has remained

essentially stagnant since 1963, according to the Census Bureau. Between 1963 and

2005, to be sure, the total number of what the Census Bureau categorizes as

families grew from 47 million to 77 million. But most of the increase is due to

families without children, including what are sometimes rather strangely called

"one-person families."

In place of traditional two-parent families with

children, America has seen enormous growth in one-parent families and childless

families. The number of one-parent families with children has tripled.

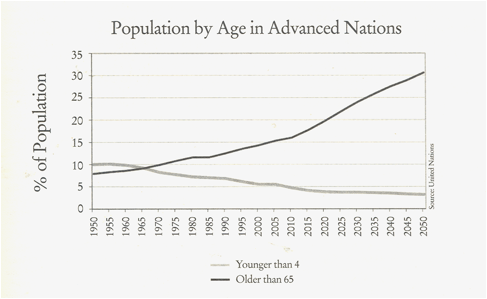

Dependent children formed half the U.S. population in 1960, and they add up to

only 30 percent today. The dependent elderly doubled as a proportion of the

population, from 15 percent in 1960 to 30 percent today.

If capital markets derive from the cycle of

human life, what happens if the cycle goes wrong? Investors may be unreasonably

panicked about the future, and governments can allay this panic by guaranteeing

bank deposits, increasing incentives to invest, and so forth. But something

different is in play when investors are reasonably panicked. What if there

really is something wrong with our future-if the next generation fails to

appear in sufficient numbers? The answer is that we get poorer.

The declining demographics of the traditional

American family raise a dismal possibility: Perhaps the world is poorer now

because the present generation did not bother to rear a new generation. All

else is bookkeeping and ultimately trivial. This unwelcome and unprecedented

change underlies the present global economic crisis. We are grayer, and less

fecund, and as a result we are poorer, and will get poorer still--no matter

what economic policies we put in place.

We could put this another way: America's housing

market collapsed because conservatives lost the culture wars even back while

they were prevailing in electoral politics. During the past half century

America has changed from a nation in which most households had two parents with

young children. We are now a mélange of alternative arrangements in which the

nuclear family is merely a niche phenomenon. By 2025, single-person households

may outnumber families with children.

The collapse of home prices and the knock-on

effects on the banking system stem from the shrinking count of families that

require houses. It is no accident that the housing market-the economic sector

most sensitive to demographics-was the epicenter of the economic crisis. In

fact, demographers have been predicting a housing crash for years due to the

demographics of diminishing demand. Wall Street and Washington merely succeeded

in prolonging the housing bubble for a few additional years. The adverse

demographics arising from cultural decay, though, portend far graver

consequences for the funding of health and retirement systems.

Conservatives have indulged in

self-congratulation over the quarter-century run of growth that began in 1984

with the Reagan administration's tax reforms. A prosperity that fails to rear a

new generation in sufficient number is hollow, as we have learned to our

detriment during the past year. Compared to Japan and most European countries,

which face demographic catastrophe, America's position seems relatively strong,

but that strength is only postponing the reckoning by keeping the world's

capital flowing into the U.S. mortgage market right up until the crash at the

end of 2007.

As long as conservative leaders delivered

economic growth, family issues were relegated to Sunday rhetoric. Of course,

conservative thinkers never actually proposed to measure the movement's success

solely in units of gross domestic product, or square feet per home, or cubic

displacement of the average automobile engine. But delivering consumer goods

was what conservatives seemed to do well, and they rode the momentum of the

Reagan boom.

Until now. Our children are our wealth. Too few

of them are seated around America's common table, and it is their absence that

makes us poor. Not only the absolute count of children, to be sure, but also

the shrinking proportion of children raised with the moral material advantages

of two-parent families diminishes our prospects. The capital markets have reduced

the value of homeowners' equity by $8 trillion and of stocks by $7 trillion.

Households with a provider aged 45 to 54 have lost half their net worth between

2004 and 2009, according to Dean Baker of the Center for Economic and Policy

Research. There are ways to ameliorate the financial crisis, but none of them

will replace the lives that should have been part of America and now are

missed.

This suggests that nothing economic policy can do

will entirely reverse the great wave of wealth destruction. President Obama

made hope the watchword of his campaign, but there is less for which to hope,

largely because of the economic impact of the lifestyle choices favored by the

same young people who were so enthusiastic for Obama. The Reagan reforms

created new markets and financing techniques and put enormous amounts of

leverage at the disposal of businesses and households. The 1980s saw the

creation of a mortgage-backed securities market that turned the American home

into a ready source of capital, the emergence of a high-yield bond market that

allowed new companies to issue debt, and the expansion of private equity. These

financing techniques contributed mightily to the great expansion of 1984-2008,

and they were the same instruments that would wreak ruin on the financial

system. During the 1980s the baby boomers were in their twenties and thirties,

when families are supposed to take on debt; twenty years later, the baby

boomers were in their fifties and sixties, when families are supposed to save

for retirement. The elixir of youth turned toxic for the aging.

Unless we restore the traditional family to a

central position in American life, we cannot expect to return to the kind of

wealth accumulation that characterized the 1980s and 1990s. Theoretically, we might

recruit immigrants to replace the children we did not rear, or we might invest

capital overseas with the children of other countries. From the standpoint of

economic policy, neither of those possibilities can he dismissed. But the

contributions of immigration or capital export will be marginal at best

compared to the central issue of whether the demographics of America reverts to

health.

Life is sacred for its own sake. It is not an

instrument to provide us with fatter IRAs or better real estate values. But it

is fair to point out that wealth depends ultimately on the natural order of

human life.

Failing to rear a new generation in sufficient

numbers to replace the present one violates that order, and it has consequences

for wealth, among many other things. Americans who rejected the mild yoke of

family responsibility in pursuit of atavistic enjoyment will find at last that

this is not to be theirs, either.

It will be painful for conservatives to admit

that things were not well with America under the Republican watch, at least not

at the family level. From 1954 to 1970, for example, half or more of households

contained two parents and one or more children under the age of eighteen. In

fact as well as in popular culture, the two-parent nuclear family formed the

normative American household. By 1981, when Ronald Reagan took office,

two-parent households had fallen to just over two-fifths of the total. Today,

less than a third of American households constitute a two-parent nuclear family

with children.

Housing prices are collapsing in part because

single-person households are replacing families with children. The Virginia

Tech economist Arthur C. Nelson has noted that households with children would

fall from half to a quarter of all households by 2025. The demand of Americans

will then be urban apartments for empty nesters. Demand for large-lot single

family homes, Nelson calculated, will slump from 56 million today to 34 million

in 2025- a reduction of 40 percent.

There never will be a housing price recovery in

many pans of the country. Huge tracts will become uninhabited except by vandals

and rodents.

All of these trends were evident for years, and

duly noted by housing economists. Why did it take until 2007 for home prices to

collapse? If America were a closed economy, the housing market would have

crashed years ago. The paradox is that the rest of the industrial world, and

much of the developing world, are aging faster than the United States.

In the industrial world, there are more than 400

million people in their peak savings years, 40 to 64 years of age, and the

number is growing. There are fewer than 350 million young earners in the

19-to40-year bracket, and their number is shrinking. If savers in Japan can't

find enough young people to lend to, they will lend to the young people of

other countries. Japan's median age will rise above 60 by mid-century, and

Europe's will rise to the mid-50s.

America is slightly better off. Countries with

aging and shrinking populations must export and invest the proceeds. Japan's

households have hoarded $14 trillion in savings, which they will spend on

geriatric care provided by Indonesian and Filipino nurses, as the country's

population falls to just 90 million in 2050 from 127 million today.

The graying of the industrial world creates an

inexhaustible supply of savings and demand for assets in which to invest

them-which is to say, for young people able to borrow and pay loans with

interest. The tragedy is that most of the world's young people live in

countries without capital markets, enforcement of property rights, or reliable

governments. Japanese investors will not buy mortgages from Africa or Latin

America, or even China. A rich Chinese won't lend money to a poor Chinese

unless, of course, the poor Chinese first moves to the United States.

Until recently, that left the United States the

main destination for the aging savers of the industrial world. America became

the magnet for savings accumulated by aging Europeans and Japanese. To this

must be added the rainy-day savings of the Chinese government, whose desire to

accumulate large amounts of foreign-exchange reserves is more than justified in

retrospect by the present crisis.

America has roughly 120 million adults in the 19-to-44

age bracket, the prime borrowing years. That is not a large number against the

420 million prospective savers in the aging developed world as a whole. There

simply aren't enough young Americans to absorb the savings of the rest of the

world. In demographic terms, America is only the leper with the most fingers.

The rest of the world lent the United States

vast sums, rising to almost $1 trillion in 2007. As the rest of the world

thrust its savings on the United States, interest rates fell and home prices

rose. To feed the inexhaustible demand for American assets, Wall Street

connived with the ratings agencies to turn the sow's ear of subprime mortgages

into silk purses, in the form of supposedly default-proof securities with high

credit ratings. Americans thought themselves charmed and came to expect

indefinitely continuing rates of 10 percent annual appreciation of home prices

(and correspondingly higher returns to homeowners with a great deal of

leverage).

The baby boomers evidently concluded that one

day they all would sell their houses to each other at exorbitant prices and

retire on the proceeds. The national household savings rate fell to zero by

2007, as Americans came to believe that capital gains on residential real

estate would substitute for savings.

After a $15 trillion reduction in asset values,

Americans are now saving as much as they can. Of course, if everyone saves and

no one spends, the economy shuts down, which is precisely what is happening.

The trouble is not that aging baby boomers need to save. The problem is that

the families with children who need to spend never were formed in sufficient

numbers to sustain growth.

In emphasizing the demographics, I do not mean

to give Wall Street a free pass for prolonging the bubble. Without financial

engineering, the crisis would have come sooner and in a milder form. But we

would have been just as poor in consequence. The origin of the crisis is

demographic, and its solution can only be demographic.

America needs to find productive young people to

whom to lend. The world abounds in young people, of course, but not young

people who can productively use capital and are thus good credit risks. The

trouble is to locate young people who are reared to the skill sets, work ethic,

and social values required for a modern economy.

In theory, it is possible to match American

capital to the requirements of young people in venues capable of great

productivity growth. East Asia, for example, has almost 500 million people in

the 19-to-40-year-old bracket, 50 percent more than that of the entire

industrial world. The prospect of raising the productivity of Chinese, Indians,

and other Asians opens up an entirely different horizon for the American

economy. In theory, the opportunities for investment in Asia are limitless, but

political trust, capital markets, regulatory institutions, and other

preconditions for such investment have been inadequate. For aging Americans to trust

their savings to young Asians, a generation's worth of institutional reforms

would be required.

It is also possible to improve America's demographic

profile through immigration, as Reuven Brenncr of McGill University has

proposed. Some years ago Cardinal Baffi of Bologna suggested that Europe seek

Catholic immigrants from Lath America. In a maH way, something like this is

happening. Europe's alternative is to accept more immigrants from the Middle

East and Africa, with the attendant risks of cultural hollowing out and

eventual Islamicization. America's problem is more difficult, for what America

requires are highly skilled immigrants.

Even so; efforts to export capital and import

workers will at best mitigate America's economic problems in a small way. We

are going to be poorer for a generation and perhaps longer. We will drive

smaller cars and live in smaller homes, vacation in cabins by the lake rather

than at Disney World, and send our children to public universities rather than

private liberal-arts colleges. The baby boomers on average will work five or

ten years longer before retiring on less income than they had planned, and

young people will work for less money at duller jobs than they had hoped.

In traditional societies, each extended family

relied on its own children to care for its own elderly. The resources the

community devoted to the destitute--

gleaning the fields alter harvest, for

example--were quite limited. Modern society does not require every family to

fund its retirement by rearing children; we may contribute to a pension fund

and draw on the labor of the children of others. But if everyone were to retire

on the same day, the pension fund would go bankrupt instantly, and we all would

starve.

The distribution of rewards and penalties is

manifestly unfair. The current crisis is particularly unfair to those who

brought up children and contributed monthly to their pension fund, only to

watch the value of their savings evaporate in the crisis. Tax and social

insurance policy should reflect the effort and cost of rearing children and

require those who avoid such effort and cost to pay their fair share.

Numerous proposals for family-friendly tax

policy are in circulation, including recent suggestions by Ramesh Ponnuru, Ross

Douthat, and Reihan Salam. The core of a family-oriented economic program might

include the following measures:

• Cut

taxes on families. The personal exemption introduced with the Second World

War's Victory Tax was $624, reflecting the cost of "food and a little more."

In today's dollars that would be about $7,600, while the current personal

exemption stands at only $3,650. The personal exemption should be raised to

$8,000 simply to restore the real value of the deduction, and the full personal

exemption should apply to children.

* Shift part

of the burden of social insurance to the childless. For most taxpayers,

social-insurance deductions are almost as great a burden as income tax.

Families that bring up children contribute to the future tax base; families

that do not get a free tide. The base rate for social security and Medicare

deductions should rise, with a significant exemption for families with

children, so that a disproportionate share of the burden falls on the

childless.

• Make

child-related expenses tax deductible. Tuition and health care are the key

expenses here with which parents need help.

• Change

the immigration laws. The United States needs highly skilled, productive

individuals in their prime years for earning and family formation.

We delude ourselves when we imagine that a few

hundred dollars of tax incentives will persuade individuals to form families or

keep them together. A generation of Americans has grown up with the belief that

the traditional family is merely one lifestyle choice among many.

But it is among the young that such a

conservative message could reverberate the loudest. The young know that the

promise of sexual freedom has brought them nothing but emptiness and anomie.

They suffer more than anyone from the breakup of families. They know that

abortion has wrought psychic damage that never can be repaired. And they see

that their own future was compromised by the poor choices of their parents.

It was always morally wrong for conservatives to

attempt to segregate the emotionally charged issues of public morals from the

conservative growth agenda. We know now that it was also incompetent from a

purely economic point of view. Without life, there is no wealth; without

families, there is no economic future. The value of future income streams

traded in capital markets will fall in accordance with our impoverished

demography. We cannot pursue the acquisition of wealth and the provision of

upward mobility except through the reconquest of the American polity on behalf

of the American family.

The conservative movement today seems weaker

than at any time since Lyndon Johnson defeated Barry Goldwater. There are no

free-marketeers in the foxholes, and it is hard to find an economist of any

stripe who does not believe that the government must provide some kind of

economic stimulus and rescue the financial system.

But the present crisis also might present the

conservative movement with the greatest opportunity it has had since Ronald

Reagan took office. The Obama administration will certainly face backlash when

its promise to fix the economy through the antiquated tools of Keynesian

stimulus comes to nothing. And as a result, American voters may be more

disposed to consider fundamental problems than they have been for several

generations. The message that our children are our wealth, and that families

are its custodian, might resonate all the more strongly for the manifest failure

of the alternatives.