SRI Secretaries in Training for Field Work

Building 320 was our second home after moving out of our tiny barracks in 404E. I think 320 might have been the old hospital morgue, but we made do. I started building spark transmitters on the roof after visiting a mad scientist in Australia named Kurt Landecker who claimed he could generate vast amount sof RF pulse power by charging capacitors in parallel and discharging them in parallel in a radiating loop or ring. Mr. Rubberband by this time had hired an exceptionally bright and highly spirited young secretary, Miss Jane Osterizer. (She later married Murray Baron but was unable to launch him into an orbit around Mars despite repeated efforts). I remember the hassles we had getting enough phones. Ray had the first speaker phone ever invented and we all used it to call friends when Ray was back East. Well another near-fatal fiasco or mine was organizing a dedication for Ray's new office. Someone (not me!) painted Ray's great oak desk flaming pink and we all recklessly filled his office with very large meteorological balloons--filled with water. As I said, this was one one several great disastrous mistakes of my life for which there is no forgiveness to be had on judgment day, and on top of that Ray was not amused. Soon after that Ma Bell announced they were doing away with phone number prefixes such as KLondike 7 or MEridian 6 and Ray decided to roll heads. Either the phone company cease and desist and leave us with our colorful history or we would take our business elsewhere, Ray told the CEO or some high muckety muck at PacBell. But our loud protests were in vain--there was only one phone company to choose from back then.

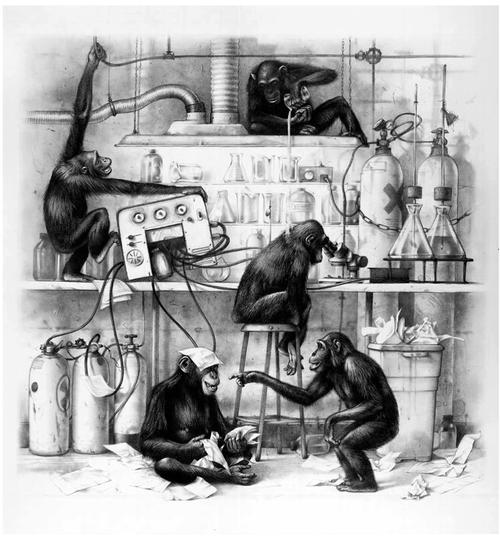

Working Environment in the 60s and 70s (typical)

We grew and grew and now the Communications Group under Vincent headed off to be their own lab and RPL marched ahead boldly. Slim Rubberband solicited all our inputs on a new Building 44. It had to have a hydraulic elevator with front and back doors and a huge High Bay capable of holding an 85 foot dish under construction and who knows how many 40-foot vans. It had sealed windows and individual thermostats with hot and cold air plenums over every office. The roof was extra strong for antenna work, but Steel Nafford had designed the high bay roof trusses so we were all a bit careful up there.

From the Menlo Park City Hall across the street the city fathers could see that we had built a respectable 2 story concrete office and lab. But secretly added was the Third Floor restauraunt featuring Joe Wagner's All-Girl orchestra with Dinner Dancing. Our ballroom could only be reached by the sticky hydraulic elevator, so access was a bit slow on Friday nights. For safety's sake Mr. Nafford built us an escape slide in the back, taken from a crashed Boeing Stratocruiser cabin door. Joseph preferred Viennese waltzes (having been raised in Austria) but RLL sent him off to dance-band school and Joe added steel drums from Antigua and other exotic instruments collected by our brilliant scientists on their world travels. Ever popular over the years, Vagner added a line of chorus girls from Stanford and belly-dancers flown in from Cairo. The latter were hand picked by our own Bob Bollen from the 23rd Floor of the SherAtone Hotel Night Club on the Nile, and most of them looked OK if the lights were kept dimmed.

|

|

Dedication date for Building 44 was a gala affair with helpful placards located throughout the building so people could find the Blue Room, the Red Room, the War Room, the restrooms, and the restauraunt. Mr. L's office was of course properly festooned with flags and banners and "What Me Worry?" posters put into place by this unnamed but well-meaning, dedicated ever-helpful lab staff member. Trouble was, Mr. Alvin Van Every from ARPA showed up for a visit on opening day and Mr. Leadabrand had to run through the building hiding signs that might be misleading to our benevolent funding agency. Not funny McGee, after all, sad to say.

It came time for more nuclear tests by our government and they

needed radar work done out in the Pacific by our lab. I flew to

Astoria, Oregon to check  out

coast guard cutters and destroyers as a possible platform and

we even inquired about an aircraft carrier (The Giant Hydrogen-filled

Dirigible-with-75 foot-steel-framework-disk-in-the-nose Project

came later). John V. N. Granger who was high up in the lab when

I came on board had his start up company going and he said his

whiz kid high school student Gordon McGinnity could build three

radars for us in 3 months. Desperate to find a practical way to

get the radars on site, Dick Stenger and I flew to Newport Beach

where yacht broker George Michaud found us the biggest and best

yacht he had--the Motor Vessel Acania--a luxury twin diesel with

teak decks built for Actress Constance Bennett in 1929. Signing

the lease Dick and I got on board and spent a very sea-sick weak

end sailing from Southern California to our berth at Treasure

Island. The ship was sturdy and sound but would roll 30 degrees

in mild swells, pitch violently when pointed into the wind and

waves, and wallow like a drunken fat lady in a following sea.

But she was fast: 10 knots! You can imagine Mr. Hilly's ire when

I sailed into port and placed a 100k of rush purchase orders the

same day. The government, Hilly said, would never allow us to

lease a ship, certainly not a yacht, and the Air Force who we

worked for by National Policy was not allowed around ships. Well,

Mr. Leadabrand rolled heads and we kept the Acania for years and

years and years! The Acania needed lots of work: air conditioning,

a 200 kw generator, a water distillation plant, fuel tanks, water

tanks--and of course five big radars all crammed into the main

salon. Stafford's 30 foot dish folded down nicely on the after

deck, the gun-mounted yagi array up front was stowable and we

even added a 75 foot cranked up tower later on for upper atmospheric

sounding with a nifty new HF step sounder. A trip to MSTS in Seattle

brought me to the office of a wonderful retired captain, Harold

Berg, who agreed to sail us to the South Pacific. Mr. Swengler

agreed to go to Hawaii for the ride and the ship left in the middle

of a great winter storm. Unlike the Titanic, the Acania was unsinkable,

but never a smooth ride, so Mr. Stenger lost 200 pounds (we think)

and was sick and forlorn when photographed at the Aloha Pier in

Honolulu after 14 days strapped into his bunk.

out

coast guard cutters and destroyers as a possible platform and

we even inquired about an aircraft carrier (The Giant Hydrogen-filled

Dirigible-with-75 foot-steel-framework-disk-in-the-nose Project

came later). John V. N. Granger who was high up in the lab when

I came on board had his start up company going and he said his

whiz kid high school student Gordon McGinnity could build three

radars for us in 3 months. Desperate to find a practical way to

get the radars on site, Dick Stenger and I flew to Newport Beach

where yacht broker George Michaud found us the biggest and best

yacht he had--the Motor Vessel Acania--a luxury twin diesel with

teak decks built for Actress Constance Bennett in 1929. Signing

the lease Dick and I got on board and spent a very sea-sick weak

end sailing from Southern California to our berth at Treasure

Island. The ship was sturdy and sound but would roll 30 degrees

in mild swells, pitch violently when pointed into the wind and

waves, and wallow like a drunken fat lady in a following sea.

But she was fast: 10 knots! You can imagine Mr. Hilly's ire when

I sailed into port and placed a 100k of rush purchase orders the

same day. The government, Hilly said, would never allow us to

lease a ship, certainly not a yacht, and the Air Force who we

worked for by National Policy was not allowed around ships. Well,

Mr. Leadabrand rolled heads and we kept the Acania for years and

years and years! The Acania needed lots of work: air conditioning,

a 200 kw generator, a water distillation plant, fuel tanks, water

tanks--and of course five big radars all crammed into the main

salon. Stafford's 30 foot dish folded down nicely on the after

deck, the gun-mounted yagi array up front was stowable and we

even added a 75 foot cranked up tower later on for upper atmospheric

sounding with a nifty new HF step sounder. A trip to MSTS in Seattle

brought me to the office of a wonderful retired captain, Harold

Berg, who agreed to sail us to the South Pacific. Mr. Swengler

agreed to go to Hawaii for the ride and the ship left in the middle

of a great winter storm. Unlike the Titanic, the Acania was unsinkable,

but never a smooth ride, so Mr. Stenger lost 200 pounds (we think)

and was sick and forlorn when photographed at the Aloha Pier in

Honolulu after 14 days strapped into his bunk.

Actually Mr.

Stenger did not exactly like the food on board the Acania. Our

cook, Hans, pictured here with Commodore Doldrums during a 30

degree roll, stored only cabbage, sauerkraut, and nachwurst in

the deck produce lockers and forepeak freezers. Enroute to the

South Pacific Stenger in a fit of unbridled frenzy threw overboard

hundreds of pounds of frozen nachwurst--poisoning fish and sharks

for miles around, and forcing our 10 man crew to eat canned chili

and peanuts from the ship's bar for the rest of the voyage. In

port, Hans stocked up just as he always had, nachwurst and cabbage.

Actually Mr.

Stenger did not exactly like the food on board the Acania. Our

cook, Hans, pictured here with Commodore Doldrums during a 30

degree roll, stored only cabbage, sauerkraut, and nachwurst in

the deck produce lockers and forepeak freezers. Enroute to the

South Pacific Stenger in a fit of unbridled frenzy threw overboard

hundreds of pounds of frozen nachwurst--poisoning fish and sharks

for miles around, and forcing our 10 man crew to eat canned chili

and peanuts from the ship's bar for the rest of the voyage. In

port, Hans stocked up just as he always had, nachwurst and cabbage.

The radars weren't all finished yet so a bunch of us joined the ship in Honolulu and rebuilt the radars radically as we sailed pitching and tossing and tolling and heaving to Entiwetok Lagoon where our tiny craft the Acania looked like a row boat alongside all the carriers and battleships of our sister projects. But we cleared port and went down to lovely Wotho atoll where we anchored awaiting for our particular bomb tests to come up on the schedule. Trips ashore helped us to appreciate native life on exotic tropical lagoons with native dancing girls. These experiences finally culminated in Alan Selby's vanishing into the culture on Raratonga in 1962 where he began to be the object of many legends and true stories that are but another part of the glorious heritage of the lab. The radars never did work right in the Marshall Islands--the time frame was simply do short to work such miracles, but the tests we were there for were delayed in time and also moved to Johnston Island so we had a reprieve in Honolulu.

Our project paper work had been hastily sent down through channels from the Highest Levels of the Pentagon and finally trickled down to Commander Field Command AF SWAP at Albuquerque. I was summoned to fly down (via TWA Constellation) to ABQ where I bonded immediately with Lt. Col. Ed. Halligan who was assigned to lead me step by step through stacks of red tape and paper work our project required in order to get us on site and relocated. I was horrified with the thought of all the paper work that had to be done right and in military jargon, too, and 12 copies. I commuted that spring (Pan Am again) some 8 times to Hawaii fixing radars and had no time to fill out forms. The Air Force did not own any ships and had no idea of fore and aft or bilge pumps and martinis on the fantail before dinner. They were in for a long, but proud learning curve and ended up with a gen-U-ine navy after all. I really liked Col. Halligan. He talked acronyms and numbers non-stop so I had to generate my own dictionary. (Mr. L. showed me the first HP hand held calculator about that time, only $395, good for adding, subtracting, multiplying, and dividing, but not yet anywhere near a Franklin language dictionary). Well, the forms got filled out for the ship's motley crew--(it turns the first crew of 10 were from the very dregs of the docks of San Francisco). Our agents, Pillsbury and Martignoni, long term SF ship chandlers, had done well for us except in the matter of our crew. But Captain Robert Fall who joined us after Entiwetok was very capable and gradually we learned how to sail the old ship as a yacht not a Liberian freighter. Roy Long ran the Acania well into the next decade getting better and better at food and amenities and congenial crew members as well as superbly functioning equipment including scuba gear and wind surfing gear of course.

![]()

Lots of money spent in haste at Honolulu shipyards and the

ship sailed a few months later with a minimal crew the 700 miles

to Johnston island while the  rest

of us flew MATS in giant drafty swaying C124 flying boxcars. We

had a bit of hassle at Hickam AFB as the passenger manifest showed

a missing man, a certain Michael Victor Acania. When we told the

desk sergeant we had sent Michael on ahead, a security crisis

of great magnitude ensued and (as I recall) we had to roust Col.

Ed Halligan out of bed in ABQ to get the Air Force Navy back on

track. We all liked JI. Our on board ship food was better, and

we had fantail luxury whereas the other projects and MPs ashore

languished in stuffy stifling hot tents and barracks with food

catering provided by Holmes and Never (pardon me, that's "Narver").

The lagoon at JI was not crystal clear as it had been at Wotho

but we enjoyed some scuba diving amongst the sea snakes, and snail

boating in our dinghies. Night and day Arch McKinley and the rest

of us fussed with radars, clip leading 30 kilovolt leads haphazardly

everywhere while squeezed in between the wet salon windows and

the huge transmitter cabinets. Mr. Leadabrand showed up on a VIP

flight in time for the big tests and we hastened to tape all the

knobs and dials in place with "No Tweaking" signs everywhere.

rest

of us flew MATS in giant drafty swaying C124 flying boxcars. We

had a bit of hassle at Hickam AFB as the passenger manifest showed

a missing man, a certain Michael Victor Acania. When we told the

desk sergeant we had sent Michael on ahead, a security crisis

of great magnitude ensued and (as I recall) we had to roust Col.

Ed Halligan out of bed in ABQ to get the Air Force Navy back on

track. We all liked JI. Our on board ship food was better, and

we had fantail luxury whereas the other projects and MPs ashore

languished in stuffy stifling hot tents and barracks with food

catering provided by Holmes and Never (pardon me, that's "Narver").

The lagoon at JI was not crystal clear as it had been at Wotho

but we enjoyed some scuba diving amongst the sea snakes, and snail

boating in our dinghies. Night and day Arch McKinley and the rest

of us fussed with radars, clip leading 30 kilovolt leads haphazardly

everywhere while squeezed in between the wet salon windows and

the huge transmitter cabinets. Mr. Leadabrand showed up on a VIP

flight in time for the big tests and we hastened to tape all the

knobs and dials in place with "No Tweaking" signs everywhere.

Flashback note: Mr. L. liked to turn knobs a lot and had previously aroused the ire of Sir Ron PreTzel in Alaska who didn't like anyone turning his dials, "Now see here, just tell me what you want and I will make it work the way you want, but no tweaking the high voltage. I am sick, sick to giant death of you guys coming in here and ruining my radars and arcing over my klystron and tracking snow and ice on my nice waxed floor. Go back to the Traveller's Inn and I'll call you when there is aurora for you to watch and you can take Polaroid pictures." The expression "Sick to Giant Death" became a watchword ever after, etched in the minds of the next generation of would be knob tweakers. Later, Hank Olsen built stuff without real knobs on front panels (they were in back) and he put lots of fake "Leadabrand knobs" on the front panel that could could be tweaked harmlessly. Sad to say, we young bucks did cause Mr. L. lots of pain and grief because he was the last of the great knob tweakers. Firing up an old APS World War I radar one day I saw him masterfully pull in clutter echoes from B29s over Berlin long after the war had ended. Ray really was good and he knew auroral echoes when he saw them. Years later when Rolf Dycehere thought he had discovered tropical aurora at Antigua during martini hour on the fantail, our Glorious Leader immediately confirmed the result and procured another million dollars from Mr. Van Every for ongoing work.

Well the nuclear tests at JI were

unforgettable. I got to stay on the ship during the events as

did Ray and our chief engineer and the Captain and a couple of

others. We fired up the 200 kw generator, and the fire pumps and

had the lifeboats checked out and ready. Everyone else was evacuated

a safe distance away and dropped on the board the Carrier USS

Boxer. Sounding rockets launched vertically upwards from the Island

came crashing around us during the test. We had carefully covered

our nice teak rails with aluminum foil in case of flash burns

and our tiny crew on board the Acania that night experienced an

unforgettable, lifechanging event which is forever etched in our

memories. Juggling finniky radars all night, and changing Dick

King's Ampex 12-channel tape reels frantically we grabbed all

the data we could, little knowing that that very data would be

studied endlessly for many years to come. The ship did not sink

and next morning I gave the Project 7.1 preliminary test report

at a meeting of Generals and Admirals and staff scientists and

rocket experts and the bomb designers. I was only 26 at the time

and certainly did not yet know which way was up. But Mr. Leadabrand

was great about delegating responsibility and he knew we would

all grow faster if we were working way over our depth with far

too much too do and no time to do it in. He allowed us to make

our own mistakes, and mine were many, frequent--and often near

disasters. Oh, yes, I need to say one word about April Weather.

We were allowed ham radio in those days and our ancient veteran

Ray Irvine was able to work the world from the South Pacific and

also send a daily "Weather Report" in the clear back

to the lab in Menlo Park. Ahead of time we had newsy codes planned

that would tell the folks at home about health and morale and

we could pass on sea sickness reports. We could also place orders

for supplies. I remember ordering one million feet of plumber's

tape one day when I was frustrated with equipment falling out

of relay racks. Good old plumber's tape was perfect, but when

the million feet arrived we had quite a time storing it ever after.

Well the nuclear tests at JI were

unforgettable. I got to stay on the ship during the events as

did Ray and our chief engineer and the Captain and a couple of

others. We fired up the 200 kw generator, and the fire pumps and

had the lifeboats checked out and ready. Everyone else was evacuated

a safe distance away and dropped on the board the Carrier USS

Boxer. Sounding rockets launched vertically upwards from the Island

came crashing around us during the test. We had carefully covered

our nice teak rails with aluminum foil in case of flash burns

and our tiny crew on board the Acania that night experienced an

unforgettable, lifechanging event which is forever etched in our

memories. Juggling finniky radars all night, and changing Dick

King's Ampex 12-channel tape reels frantically we grabbed all

the data we could, little knowing that that very data would be

studied endlessly for many years to come. The ship did not sink

and next morning I gave the Project 7.1 preliminary test report

at a meeting of Generals and Admirals and staff scientists and

rocket experts and the bomb designers. I was only 26 at the time

and certainly did not yet know which way was up. But Mr. Leadabrand

was great about delegating responsibility and he knew we would

all grow faster if we were working way over our depth with far

too much too do and no time to do it in. He allowed us to make

our own mistakes, and mine were many, frequent--and often near

disasters. Oh, yes, I need to say one word about April Weather.

We were allowed ham radio in those days and our ancient veteran

Ray Irvine was able to work the world from the South Pacific and

also send a daily "Weather Report" in the clear back

to the lab in Menlo Park. Ahead of time we had newsy codes planned

that would tell the folks at home about health and morale and

we could pass on sea sickness reports. We could also place orders

for supplies. I remember ordering one million feet of plumber's

tape one day when I was frustrated with equipment falling out

of relay racks. Good old plumber's tape was perfect, but when

the million feet arrived we had quite a time storing it ever after.

I do want to mention our dear colleague Dr. Rolf Dycehere, a really bright young scientist just coming into puberty whom Mr. Leadabrand had adopted on one of his trips back East. I think Dycehere had been to Cornell or Lincoln Labs and it was said he knew the great Gordon Pettingill and had actually seen the Lincoln labs radar dome in person. The photo at right taken using one of our scope cameras shows Murray Baron disguised to look like Dr. Dycehere reading an inflammatory cheap pulp sci-fi novel. Rolf was actually outside at the pier waiting for the boat out to his riometer shack on a remote island. In the background Mr. PreTzel mans the radar controls and in the rear J. Loren Dye is obviously soldering something under the total masterful direction of the Radar Master. The van may look cozy (it had cots in back) and it was very hot with 100% humidity outside, but Ron kept the air conditioning blasts at near zero which he found comfortable even with shorts on, unlike the rest of us. Dr. Dycehere always wore shorts even at high level meetings in the Pentagon. "Oh dear me, my goodness, Ray, I seem to have lost my riometer charts. Can you hand me that match cover and a pen and I'll scribble the curves out here so General Folderol here can see the absorption in the D layer caused by overflying goonie birds." "Well, I don't know I never thought about that I suppose we would jury rig a scarecrow to keep the damn (excuse me, Ray that was not polite of me) birds off my antennas." Rolf did great work later on, raking leaves out from under the crater dish at Arecibo and sweeping the catwalk out to the feed point. We are reminded that a good scientist is not ashamed to sweep out his van and change the ink wells on the chart recorders.

The next round of tests at JI in '62 were more sane as far as lead time, and more sensible equipment-wise as Ron PreTzel had time to build good radars and Holmes and Never built us a new big dish on JI after new specs from the ever creative Steel Nafford (his collection of match cover sketches is, we think, in the Foothill Electronics history museum). The next nuclear test series under the direction of General Birdseed (sp?) was frustrating and long drawn out. I snitched a piece of blown up Redstone missile fuel pump from the runway after one failed test, and Mr. R. still uses it to this day as a radioactive paperwork as I recall. Dr. Water Closet assumed a major role behind the scenes about that time. He kept four secretaries busy at all times and was the perfect model of a brilliant, eccentric, dazzlingly gifted --but not always practical--great scientist we could all emulate. When I was around him I always wished I could remember my freshman physics a bit better. I always had a hard time about these guys with brains. It never bothered Ray that he had flunked French and was almost, but not quite a real doctor, but in a way I always wished I had stayed on at Stanford for another decade and had Mr. Chan tutor me until I passed all my comp exams. Still, I would have missed a lot of swashbucking adventure had I done so, and a lot of PhDs I met were really quite dull and boring people.

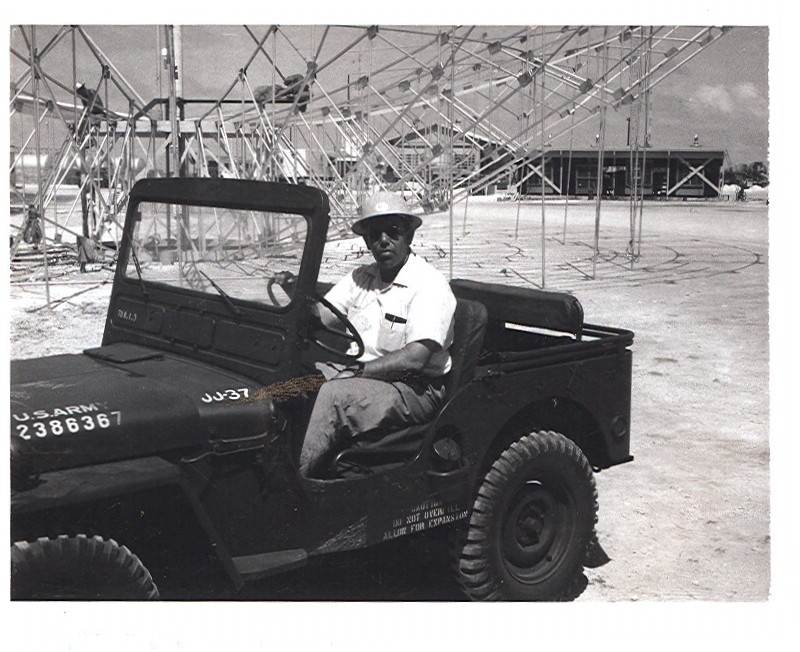

Sir Neil Stafford at Johnston Island about 1962 or so.