Fiat Money

The End of Fiat Currency (Britt Gillette)

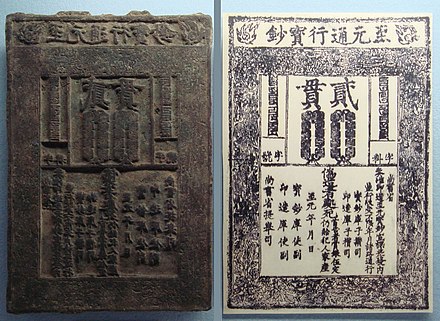

Yuan dynasty banknotes are a medieval form of fiat money.

|

| Country | Year |

|---|---|

| United Kingdom | 1821 |

| Germany | 1871 |

| Sweden | 1873 |

| United States (de facto) | 1873 |

| France | 1874 |

| Belgium | 1874 |

| Italy | 1874 |

| Switzerland | 1874 |

| Netherlands | 1875 |

| Austria-Hungary | 1892 |

| Japan | 1897 |

| Russia | 1898 |

| United States (de jure) | 1900 |

An early form of fiat currency in the American Colonies was "bills of credit." Provincial governments produced notes which were fiat currency, with the promise to allow holders to pay taxes with those notes. The notes were issued to pay current obligations and could be used for taxes levied at a later time. Since the notes were denominated in the local unit of account, they were circulated from person to person in non-tax transactions. These types of notes were issued particularly in Pennsylvania, Virginia and Massachusetts. Such money was sold at a discount of silver, which the government would then spend, and would expire at a fixed date later.

Bills of credit have generated some controversy from their inception. Those who have wanted to emphasize the dangers of inflation have emphasized the colonies where the bills of credit depreciated most dramatically: New England and the Carolinas. Those who have wanted to defend the use of bills of credit in the colonies have emphasized the middle colonies, where inflation was practically nonexistent.

Colonial powers consciously introduced fiat currencies backed by taxes (e.g., hut taxes or poll taxes) to mobilise economic resources in their new possessions, at least as a transitional arrangement. The purpose of such taxes was later served by property taxes. The repeated cycle of deflationary hard money, followed by inflationary paper money continued through much of the 18th and 19th centuries. Often nations would have dual currencies, with paper trading at some discount to money which represented specie.

Examples include the “Continental” bills issued by the U.S. Congress before the United States Constitution; paper versus gold ducats in Napoleonic era Vienna, where paper often traded at 100:1 against gold; the South Sea Bubble, which produced bank notes not representing sufficient reserves; and the Mississippi Company scheme of John Law.

During the American Civil War, the Federal Government issued United States Notes, a form of paper fiat currency known popularly as 'greenbacks'. Their issue was limited by Congress at slightly more than $340 million. During the 1870s, withdrawal of the notes from circulation was opposed by the United States Greenback Party. It was termed 'fiat money' in an 1878 party convention.

20th century

After World War I, governments and banks generally still promised to convert notes and coins into their nominal commodity (redemption by specie, typically gold) on demand. However, the costs of the war and the required repairs and economic growth based on government borrowing afterward made governments suspend redemption by specie. Some governments were careful of avoiding sovereign default but not wary of the consequences of paying debts by consigning newly printed cash not associated with a metal standard to their creditors, which resulted hyperinflation – for example the hyperinflation in the Weimar Republic.

From 1944 to 1971, the Bretton Woods agreement fixed the value of 35 United States dollars to one troy ounce of gold. Other currencies were calibrated with the U.S. dollar at fixed rates. The U.S. promised to redeem dollars with gold transferred to other national banks. Trade imbalances were corrected by gold reserve exchanges or by loans from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The Bretton Woods system was ended by what became known as the Nixon shock. This was a series of economic changes by United States President Richard Nixon in 1971, including unilaterally canceling the direct convertibility of the United States dollar to gold. Since then, a system of national fiat monies has been used globally, with variable exchange rates between the major currencies.

Precious metal coinage

During the 1960s, production of silver coins for circulation ceased when the face value of the coin was less than the cost of the precious metal it contained (whereas it had been greater historically ). In the United States, the Coinage Act of 1965 eliminated silver from circulating dimes and quarter dollars, and most other countries did the same with their coins. The Canadian penny, which was mostly copper until 1996, was removed from circulation altogether during the autumn of 2012 due to the cost of production relative to face value.

In 2007, the Royal Canadian Mint produced a million dollar gold bullion coin and sold five of them. In 2015, the gold in the coins was worth more than 3.5 times the face value.

Money creation and regulation

A central bank introduces new money into an economy by purchasing financial assets or lending money to financial institutions. Commercial banks then redeploy or repurpose this base money by credit creation through fractional reserve banking, which expands the total supply of "broad money" (cash plus demand deposits).

In modern economies, relatively little of the supply of broad money is physical currency. For example, in December 2010 in the U.S., of the $8,853.4 billion of broad money supply (M2), only $915.7 billion (about 10%) consisted of physical coins and paper money. The manufacturing of new physical money is usually the responsibility of the national bank, or sometimes, the government's treasury.

The Bank for International Settlements published a detailed review of payment system developments in the Group of Ten (G10) countries in 1985, in the first of a series that has become known as "red books". Currently the red books cover the participating countries on Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (CPMI). A red book summary of the value of banknotes and coins in circulation is shown in the table below where the local currency is converted to US dollars using the end of the year rates. The value of this physical currency as a percentage of GDP ranges from a maximum of 19.4% in Japan to a minimum of 1.7% in Sweden with the overall average for all countries in the table being 8.9% (7.9% for the US).

| Country | Billions of dollars | Per capita |

|---|---|---|

| United States | $1,425 | $4,433 |

| Eurozone | $1,210 | $3,571 |

| Japan | $857 | $6,739 |

| India | $251 | $195 |

| Russia | $117 | $799 |

| United Kingdom | $103 | $1,583 |

| Switzerland | $76 | $9,213 |

| Korea | $74 | $1,460 |

| Mexico | $72 | $599 |

| Canada | $59 | $1,641 |

| Brazil | $58 | $282 |

| Australia | $55 | $2,320 |

| Saudi Arabia | $53 | $1,708 |

| Hong Kong SAR | $48 | $6,550 |

| Turkey | $36 | $458 |

| Singapore | $27 | $4,911 |

| Sweden | $9 | $872 |

| South Africa | $6 | $113 |

| Total/Average | $4,536 | $1,558 |

The most notable currency not included in this table is the Chinese yuan, for which the statistics are listed as "not available".

Inflation

The adoption of fiat currency by many countries, from the 18th century onwards, made much larger variations in the supply of money possible. Since then, huge increases in the supply of paper money have occurred in a number of countries, producing hyperinflations – episodes of extreme inflation rates much greater than those observed during earlier periods of commodity money. The hyperinflation in the Weimar Republic of Germany is a notable example.

Economists generally believe that high rates of inflation and hyperinflation are caused by an excessive growth of the money supply. Presently, most economists favor a small and steady rate of inflation. Small (as opposed to zero ormnegative) inflation reduces the severity of economic recessions by enabling the labor market to adjust more quickly to a recession, and reduces the risk that a liquidity trap (a reluctance to lend money due to low rates of interest) prevents monetary policy from stabilizing the economy.However, money supply growth does not always cause nominal increases of price. Money supply growth may instead result in stable prices at a time in which they would otherwise be decreasing. Some economists maintain that with the conditions of a liquidity trap, large monetary injections are like "pushing on a string."

The task of keeping the rate of inflation small and stable is usually given to monetary authorities. Generally, these monetary authorities are the national banks that control monetary policy by the setting of interest rates, by open market operations, and by the setting of banking reserve requirements

Loss of backing

A fiat-money currency greatly loses its value should the issuing government or central bank either lose the ability to, or refuse to, continue to guarantee its value. The usual consequence is hyperinflation. Some examples of this are the Zimbabwean dollar, China's money during 1945 and the Weimar Republic's mark during 1923. A more recent example is the currency instability in Venezuela that began in 2016 during the country's ongoing socioeconomic and political crisis.

But this need not necessarily occur, especially if a currency continues to be the most easily available; for example, the pre-1990 Iraqi dinar continued to retain value in the Kurdistan Regional Government even after its legal tender status was ended by the Iraqi government which issued the notes.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Gold Notes

The Temple of Solomon and its Gold

Riches!

Now godliness with contentment is great gain.

For we brought nothing into this world,

and it is certain we can carry nothing out.

And having food and clothing, with these we shall be content.

But those who desire to be rich fall into temptation and a snare,

and into many foolish and harmful lusts

which drown men in destruction and perdition.

For the love of money is a root of all kinds of evil,

for which some have strayed from the faith in their greediness,

and pierced themselves through with many sorrows.

But you, O man of God, flee these things and pursue righteousness,

godliness, faith, love, patience, gentleness.

(1 Timothy 6:6-11)

Lambert's Main Library

Email is welcome: Lambert Dolphin

Archive for Newsletters

Library Annex (new articles since 2018)

Newsletter #44 March 2022

December 8, 2022