"Mirror, Mirror on the Wall..."

Prize Winning Photo of youthful Project leader at Stanford Field Site, 1955.

"Mirror, Mirror on the Wall..."

Prize Winning Photo of youthful Project leader at Stanford

Field Site, 1955.

We all drove to and from the Stanford Village, the headquarters of SRI, and the field site in an ancient 4X4 all purpose humungous vehicle and we had to negotiate locked gates which were zealously guarded by one Immanuel Peers ("Farmer Peers"). Peers had a dairy and grazed his cows on leased land from Stanford, and had done so for generations as far as I knew. "You guys be real careful and don't let the bulls in with the cows. Next time I'll get my shot gun." "I plead guilty sir, we will be more careful next time," I promised when the inevitable happened and Farmer Peers' herd took a quantum jump in size. Peers was a neat guy--on Sundays he took his friends fox hunting at the field site--everyone all dressed in English riding style. I think the dairy is still there?

Well them early days was already getting hectic. It seems Dr.

Alec Montflower Patterson had gone to the Pentagon and come home

with a portfolio of big, important projects the government wanted

done yesterday--in order to fend off impending nuclear war with

the Russians. I knew how to spend money and Mr. Rubberband knew

how to roll heads! (He was awesome). His arch opponent in Upper

Management, Ray's Simon Lagree, was our very proper ever-beloved

by-the-book ever-foot-dragging Chuck Hilly. Oh, yes, I forgot

to introduce Gordon Rosekilly, of Rosekilly Machinery, San Mateo,

who was always at my door to sell us junk. (see photo). When Frank

Firth built our first hi-powered TR switch, Mr. Rosekilly immediately

delivered a wonderful 1930 model Rootes Blower, which  upon

being demonstrated, spewed dirty oil and fumes all over our lab.

Omar Spain was SRI Facilities Manager, Walter Jaye was our effective

rising manager type, and well so far you have met the rest of

the illustrious team members in the above photo as they all met

for a High Level meeting in 1957. Yours truly is shown wearing

the ever-popular official Lab tee shirts with a portrait of our

Great Leader, Mr. Rubberband, and the helpful reminder "What

Me Worry?" which was later stolen, rumor has it, by Mad Magazine.

They made lots of bucks on our logo that's for sure.

upon

being demonstrated, spewed dirty oil and fumes all over our lab.

Omar Spain was SRI Facilities Manager, Walter Jaye was our effective

rising manager type, and well so far you have met the rest of

the illustrious team members in the above photo as they all met

for a High Level meeting in 1957. Yours truly is shown wearing

the ever-popular official Lab tee shirts with a portrait of our

Great Leader, Mr. Rubberband, and the helpful reminder "What

Me Worry?" which was later stolen, rumor has it, by Mad Magazine.

They made lots of bucks on our logo that's for sure.

The radar went together fairly smoothly. Leadabrand wanted more power so we doubled the voltage on the final RF power amp and cranked up the front-end drive to overload. ("More drive, I want more drive..." Ray always said.). The outside 440-volt circuit breaker was not too reliable and when some gigantic arc-overs threatened to burn up the transmitter, van and all, our wonder boy engineer Ronald PreTzell rigged up a giant golden watch fob (a solenoid, heavy weight and chain) to the Panic buttons so we could kill all the power if we had to. Running the transmitter way beyond Westinghouse specs was hairy at times, with corona buzzing in the back room and the coax feeds arcing over in the night sky--but the data came in and we had amazing radar echoes from the moon. Meteors, too showed up nicely on the screen.

The proposed SRI Giant Hydrogen-Filled Steel Framework Dirigible (GHFSFD) with 75 foot foot dish and spark gap radars, compared with a sleazy 747 and the ill-fated Titanic. Match cover sketch by Steel Nafford. |

When it came time to build more dishes we were ready. The second major GSFD, 150 feet in diameter, was another masterpiece conceived by Steel Nafford, and built face up on the ground. It was finally lifted onto its mounts by L.L. Bean Rigging Company using the two largest cranes in the Bay Area on a Sunday morning. This disk was light weight and cheap compared to the million dollar precision dishes the Andrew Corp was building everywhere by that time. Mr. Dewey Bunson Berner from Hiller Helicopters of East Palo Alto came along to help Neil Stafford build the light weight dish proper. It was built of aluminum struts inward and outward from a giant steel ring. Sir George Durfey, ever resourceful, adapted Navy gun turret hydraulic drives to turn the thing around on its circular railroad track and soon young Murray Barroom had a PDP11 tracking computer installed and the disk was ready. Noise levels being high at Stanford the disk found limited usefulness for receiving but continues to be useful to the present day mostly for impressing out of town visitors and potential clients. And, it is the prototype for others of its kind, one of which was sent to Scotland which allowed our very own boy scientists Schlow Johnbohm an opportunity to rent a castle and go after high latitude auroral echoes. I got to go to Adelaide and Woomera to plan for our 85 foot disk there and came back a confirmed tea drinker and a temporary Australian accent. And so on, and on and on...

![]()

|

Our Ever-Inspiring Glorious

Leader

|

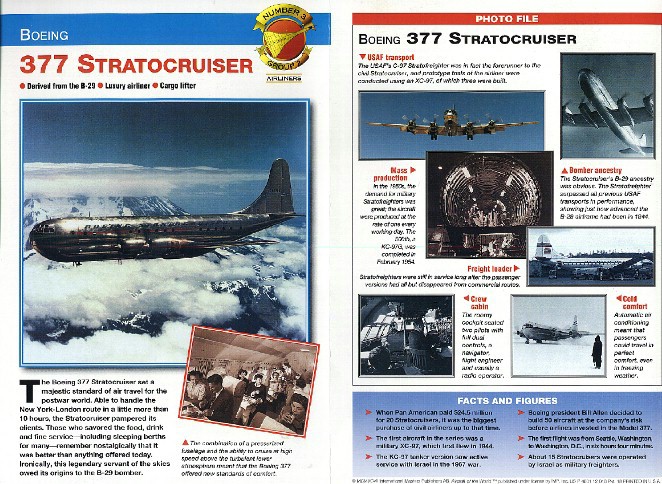

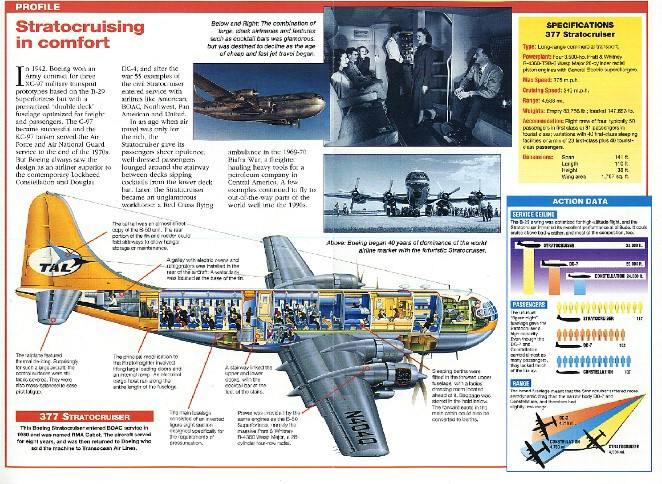

My first ride in an aeroplane was in 1956. Mr. Leadabrand said I could go to Fairbanks with him. Our Western Airlines DC6b zoomed us up to Seattle where we boarded--at midnight--the Pandemonium World Scareways flight to Alaska. PanAm was really classy in those days with stewards and stewardii upstairs and downstairs in their giant luxury liners--tri-motored Boeing Stratocruisers (converted WW2 bombers). At first I did not understand the tri-motor appellation until I found out that these four-motored planes with their 10 foot 4-bladed props were grossly underpowered, almost always always lost an engine on take off--or half way across the Pacific from a runaway prop--and they were said not to be able to fly on three. Fifty-five gallons of oil went with each engine and all of this ended up splattered on fuselage and windows after a typical flight, dimming one's night time view of the white hot exhaust manifolds. The Stratocrusers were certainly quiet inside and the seats were lush and padded so the fact that we were lucky to get 200 knots was acceptable. J. Loren Dye later kept a log book of the names painted on the front of these PanAm planes: The Seven Seas, The Northern Lights, The Queen of the Skies, The Monarch of the Skies, The Southern Cross, and we all kept track of which plane we were on whenever we flew--until Loren found out that whenever PAA lost a plane at sea they seemed to just shift the names around so no one was the wiser.

On my very second Stratocruiser flight we lost an engine and

landed at Bellingham. Years later flying from the Marshall islands

to Hawaii in a military version a C97 our engine-out experience

diverted us to a long miserable wait for repairs at Guam. But

the pilot led me come up front in the flight and the view out

the front was superb--great windows from floor to ceiling. The

early days of flying for SRI got better when DC7s came along.

They were very loud but much faster. One could fly all night to

DC on the red-eye special, work all day at the  Pentagon and fly home via a refueling

stop in Chicago that same day. Ray thought we young engineers

should commute back east at least once a month just to keep fit.

Finally the luxurious Lockheed Super Cancellations came along

with their very reclining seats and faster turbo-charged ride.

I shall never forget my first 707 ride--New York to Miami in the

days when PanAm had the only jet flight in the country. Shortly

after that TWA started their 2:15 PM daily trip from SFO to Dulles

and crowds lined up at the airport to watch a real, live 707 take

off after using up all the runway and water injection besides.

It was a long wait before Travel could get us reservations.

Pentagon and fly home via a refueling

stop in Chicago that same day. Ray thought we young engineers

should commute back east at least once a month just to keep fit.

Finally the luxurious Lockheed Super Cancellations came along

with their very reclining seats and faster turbo-charged ride.

I shall never forget my first 707 ride--New York to Miami in the

days when PanAm had the only jet flight in the country. Shortly

after that TWA started their 2:15 PM daily trip from SFO to Dulles

and crowds lined up at the airport to watch a real, live 707 take

off after using up all the runway and water injection besides.

It was a long wait before Travel could get us reservations.

Well this true story is not about airplanes, actually. We all had tales to tell about flying because it was not long before Mr. R. and Mr. Vincent had projects all over the world and we all got to fly all the time. Since we had been told that work was fun we never doubted our great leader's call for more drive, or his cry "Faster" uttered in the halls ways when work seemed to be slowing down. But speaking of flying. a careful observer noted that Dr. Patterson could not be both in Washington DC briefing the President and Joint Chiefs AND teaching classes and running Engineering projects at SRI all simultaneously. Aftre hiring a private eye we learned that there existed two identical Dr. Pattersons, affectionately known as "I" and "II"--and that (quantum mechanically speaking) the average position of either of the two Dr. Petes was 35,000 feet over Kansas City at any given time. A portrait of our Founder and Very Great High Glorious Leader (F&VGHGL) found its way into the lobby where is probably resides to this day?

Came time to take the Stanford 61 foot dish to Fairbanks. It all got shipped by barge and rail and truck, and arrived in the dead of winter so Mr. Leadabrand and I went up and assembled the dish upside down in the snow, and with a little help we tied on the screen, too. A couple of months later J. Loren Dye and I went up to connect the dish to the mount. Our first exciting adventure was meeting Bud Hilton of Hilton's SteamThawing Service. Seems as if 40 below in Fairbanks can be troublesome if you want to pour concrete or get frozen snow off of a radar dish, but Bud showed up with truck and huge boiler and set us free in short order midst clouds of steam and artificial ice fog. It was at the Geophysical Institute that I first met a very nice grad student in wool shirts and jeans by the name of Bob Leonard. A young lady named Carol and Bob and a bunch of us from SRI took a trip down to Nenanna to see an old gold dredge on the Tanana River that winter--all lots of fun. In winter the sun comes up in Fairbanks in late morning, it grazes the southern sky and night sets in about 4 PM. There is not a lot else to do. We did eat well at the Fairbanks Inn, always on the look out for our favorite waitress, Miss Structurally Unsound, whose hour-glass figure narrowed at the waist to the vanishing point. We made jokes about our favorite bars being open 24 hours and since it was hard to tell when it was not night we could stay out too late all too easily. "Did I see the Institute vehicle parked in front of the Diamond Horsehoe again last night" asked someone from the Geophysical Institute on several occasions.

|

Mr. Leadabrand commends our Large Scale organ builder, Dick Stenger, who has just given a wonderful performance on a real steam calliope in the High Bay of Bldg 44. About 1972 I think. |

Dedication speech by Slim Rubberband presenting authentic photo of our Glorious Founder, Alex Montflower Patterson I, II, to Commodore Lumbar Doldrums on the occasion of Doldrums sabbatical leave. |

Young Dick Stenger, one of our all time best and most ingenious technicians was also the Large Scale Organ builder for Casavant Freres of Montreal had earlier he had introduced Roy Long and me to the wonderful world of pipe organs. We three, with organist C. Thomas Rhoads often visited all the major Bay Area theaters after the last movie show and climbed the organ lofts, and in fact we gave away a year of weekends restoring the Wurlitzer theater organ at the Lost Weekend Bar at 19th and Taraval in San Francisco for musician Larry Vannucci who became a dear friend. Roy even flew us in his overloaded Cessna to LA for a full weekend of church organ touring.

Well

anyhow it was while Dick and J. Loren and I were in Fairbanks

that we discovered that the Empire Theater had a pipe organ left

over from the silent film days! Naturally we dropped out vital

government project work and got the old Hope Organ playing again.

The above libelous, untrue, fictional story by Jim Hodges borrows

an actual daguerreotype of the work underway at 2 AM in the Empire

Theater where our visionary leader Lumbar is vacuuming stale popcorn

from the main pipe chest. Stenger was at the console at the time

testing the hydraulic lift which was gummed up with old coca cola.

In all fairness, Mr. Hedges is a likable, congenial person but

he always got his facts mixed up trying to make up the funniest

stories to post outside of the Lab Manager's office and later,

upstairs, on the Lambert Dolphin Memorial Bulletin Board. Mr.

Hodges was well intentioned, we do acknowledge that fact. Anecdotally,

I think it worthwhile to mention my meeting with the Fairbanks

Chamber of Commerce and Ladies Aid society in Fairbanks in the

early years (see photo, right). In a press interview describing

the wonders of streaming charged particles from the sun becoming

trapped in the magnetic field lines and ending up in Alaska, Dr.

Patterson's remarks at a public meeting at Traveler's Inn had

caused some careless, unnamed reporter to write that Dr. Patterson

had come to their state with a new machine that could "turn

off the aurora." The ensuing alarm and phone calls to E.

Kinley Karter, SRI president, necessitated a series of home meetings

to calm the local populace.

Well

anyhow it was while Dick and J. Loren and I were in Fairbanks

that we discovered that the Empire Theater had a pipe organ left

over from the silent film days! Naturally we dropped out vital

government project work and got the old Hope Organ playing again.

The above libelous, untrue, fictional story by Jim Hodges borrows

an actual daguerreotype of the work underway at 2 AM in the Empire

Theater where our visionary leader Lumbar is vacuuming stale popcorn

from the main pipe chest. Stenger was at the console at the time

testing the hydraulic lift which was gummed up with old coca cola.

In all fairness, Mr. Hedges is a likable, congenial person but

he always got his facts mixed up trying to make up the funniest

stories to post outside of the Lab Manager's office and later,

upstairs, on the Lambert Dolphin Memorial Bulletin Board. Mr.

Hodges was well intentioned, we do acknowledge that fact. Anecdotally,

I think it worthwhile to mention my meeting with the Fairbanks

Chamber of Commerce and Ladies Aid society in Fairbanks in the

early years (see photo, right). In a press interview describing

the wonders of streaming charged particles from the sun becoming

trapped in the magnetic field lines and ending up in Alaska, Dr.

Patterson's remarks at a public meeting at Traveler's Inn had

caused some careless, unnamed reporter to write that Dr. Patterson

had come to their state with a new machine that could "turn

off the aurora." The ensuing alarm and phone calls to E.

Kinley Karter, SRI president, necessitated a series of home meetings

to calm the local populace.

"Put the book down Daniel, Roy needs you.

Lambert has crashed the KL10 again"

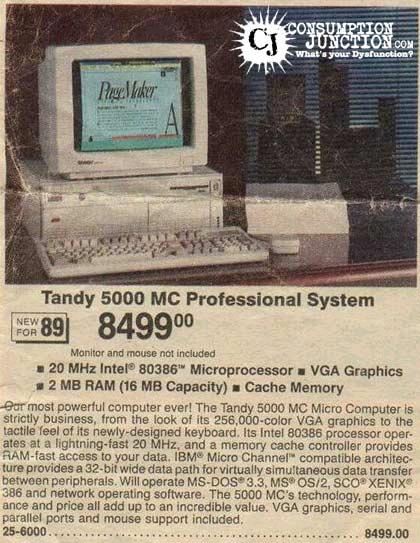

SRI New Years' Party CA 1955

Ray Irvine at the Piano